Living the Moment, a Timestamp!

Boys will be Boys

|

R |

oaches, and most rodents for that matter, have a much shorter lifespan than we do. I wonder, though, if that truly means they live any less. In fact, couldn't they live more in a day than we do in a lifetime? I don’t really know the answer, of course, but I’ve often toyed with the idea. One of my first memories of this, in fact, dates back to my days in North Miami, when my brother and I, both teenagers and both blind to consequences, played, raced, and misbehaved at the drop of a hat.

I must’ve been thirteen years old, and my brother seventeen. We both attended Lear School. It was an elementary, junior high, and high school all rolled into one, located on Biscayne Boulevard, next to the Jockey Club, which was a prestigious country club to which we didn’t belong. Anyway, my parents were out of the country visiting our grandparents back in Venezuela and my brother and I were on our own for about a week and a half to two.

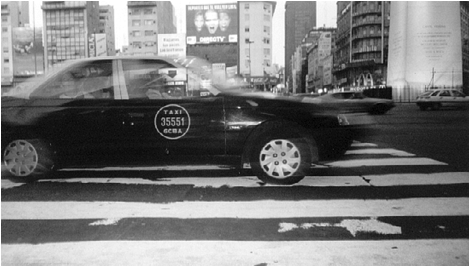

After school, and after soccer practice, around six o’clock, we’d always meet our friends and hang out and “shoot the breeze,” so to speak, but not before we raced our way there. Driving up and down Biscayne Boulevard was an adventure, and we enjoyed every minute of it. It was a heavily trafficked, five-lane, two-way street, with a turning lane in the middle, and grass bordering it on both sides. We were all a bunch of maniacs on the road, and we constantly fulfilled our “need for speed” and our appetite for danger. We raced almost daily and frequently met our friends afterwards at someone’s house, or at the beach by Haulover Park. Mauricio (another Venezuelan) was the craziest of us all. He’d swerve in and out of traffic with ease and foresight, and without fear or hesitation. He’d pass cars on the turning lane and, if circumstances were favorable, he’d also jump over to oncoming traffic to inch his way closer to pole position. Of course, he’d complement that by driving over the grass and on top of the median, wherever he could fit his two-door Honda, or Toyota, or whatever it was.

As for my brother and I, we were a team. We rode in our dad's two-door, 6-cylinder, 2.5-liter, black Buick Century, which, back then, felt really powerful to us. Being that I was too young to drive legally, I filled the role of copilot. I studied traffic patterns and determined the best times to change lanes and what cars to follow. I’d often look at the driver of the vehicle in front of us and, based on his or her appearance, temperament, and reactions, determine what kind of driver he or she was, for example, passive, predictable, insecure, assertive, precise, distracted, absent minded, etc. I also read their gestures and driving habits and predicted if they were about to change lanes or turn. I used all this information to formulate a game plan and consequently recommend lane changes. With a proven record over the span of many months, my brother and I gained each other’s trust. He was confident in my ability to stitch together a winning plan and I knew he was capable of executing it to a T. He was, and still is, a good driver, and that is how we often beat our friends.

One Friday afternoon, on one of those days when we didn’t have soccer practice, we left school at about three o’clock in the afternoon and agreed to meet Robert and Steve somewhere on Collins Avenue, by the Intracoastal. The plan was to drive north on Biscayne Boulevard, as usual, and go east on 163rd Street towards the beach. So the race began…and off we went!

“Change to the right lane after the blue truck. The red Camaro in front of the truck is about to turn right and free that lane for us. Come on!”

“How far in front of us is Robert?”

“We’re okay, I think, but we can't make any mistakes. Look to get out of this lane, by the way, because the bus half a block ahead of us could make a stop and we don’t want to get stuck at the light after that.”

Robert and Steve, who drove a yellow 300 SEL Mercedes, were ahead of us by a short distance. We were still on Biscayne Boulevard when we almost caught up. We were barely three to four car-lengths shy of their tail and just short of the light at 163rd Street. Unfortunately, 163rd Street didn’t have much traffic on its three eastbound lanes. I say “unfortunately” because we used traffic and strategic lane changes to edge out our competition. On straight-aways, without pronounced turns or heavy traffic, our respective engines and our willingness to speed determined the outcome of the race – there was no need for a well-formulated plan under those conditions.

Well…we turned onto 163rd Street and punched it. Now we were about thirty yards behind the Mercedes. There were probably three to four other cars driving on the road, which was not enough to warrant much planning on my part, especially on a three-lane highway. I don’t remember how fast we traveled through the straight-away, but we neared, at one point, what seemed like 125 miles per hour. There were two traffic lights prior to the Intracoastal – the finish line – and we were quickly approaching the first one.

“Get in the right lane. The light is just turning yellow and I’m sure Robert will drive on through.”

We must’ve been one hundred yards away when I said that. Three cars, all in the left two lanes, slowed down and stopped. Robert's brake lights then ignited and he started slowing down when…

“Hermano, he’s stopping! He’s stopping!”

Robert (the freaking fool) decided to make a complete stop, when he’d normally never do so, not even when he wasn’t racing. Obviously, my brother realized this and started breaking, but the car just seemed to slide. The car glided like a bobsled skidding on ice. He pumped the brakes, leaned on the parking brake, and down-shifted gears. The engine jumped and coughed, but we had too much momentum to stop and too much speed to fight it. My brother and I looked at each other, and without uttering a word, we knew exactly what both of us were thinking…

“A Mercedes Benz is much more expensive than a Plymouth…”

My brother nodded and steered toward the center lane, toward the blue, unsuspecting Reliant…

Dsssssssssssssssssssssssssss…BBPPPuhhgrrrrrrrrrrrrnnnng…

I won’t attempt to fully describe what went through our heads as we first thought of ways to hide the accident from my parents. As the reader can imagine, we thought of convincing the lady driver to let us go without calling the police, and of leaving the scene of the accident, which obviously would’ve made us teenage fugitives. But we didn’t…

What I will tell you, though, which is the point of the story, is how much I lived in those two to three seconds before the dreaded collision, just before the point of impact. I remember everything, from my brother’s frown, his wide-open, puppy brown eyes, and his brusque yet controlled maneuvers to the approaching cars and our inevitable fate. We only had one choice to make and we picked our only viable recourse – as we saw it – while consulting amongst ourselves and consoling each other in the process. I remember the car sliding and the wheels locking, but the tires never squealed. It was morbidly silent. I also remember looking at my brother and at the oncoming Reliant, back and forth, while tightly gripping the cold dashboard with my right hand and the thin center consul with my left. I was ready for the impact we were about to endure, and hopefully survive – but that, too, we wondered about. Everything occurred in hyper slow motion.

I also thought of my parents and how outraged they’d become, especially my dad. I remember thinking of how much money I had saved up (I had a little over three hundred dollars to my name, which I had saved in an Amerifirst bank account). Maybe Robert would lend us some money, and along with my brother’s savings, we’d be able to pay for the damages of both cars. All these thoughts crossed my mind as we slid, except I'm ashamed to say, the passengers of the Plymouth. We didn’t think about the poor middle-aged woman with her three innocent children. They really never crossed our minds.

So, could an insect truly have a fulfilling life in just twenty-four hours? Well, if it were to live it in its entirety just like I lived those few moments before the crash…Yes, most definitely! It may end up living a fuller life, in fact, filled with the intensity of a thousand lives. Without our visual, thirty-or-so frames-per-second restriction, perceived time, or shall I say, real time is unbounded, without limits. When it comes right down to it, there’s an infinite amount of time between every second, but we’re incapable of perceiving it, much less living it. We, like all other living things, only recognize finite chunks of time, which constitute only a fraction of the happenings around us.

As to my brother and me, the police came and drafted a report, and they pronounced my brother guilty on the spot. My dad’s insurance paid for everything. The Plymouth had to pretty much be rebuilt. I imagine my dad’s premium went through the roof. The damage was on the order of several thousands of dollars. There’s no way my brother and I would’ve been able to pay for it, even with Robert’s help. My dad returned home from Venezuela early because of our accident and didn’t say a word to either of us for at least six weeks. Thankfully, the children in the Plymouth were okay, and so was their mother, but what if they hadn’t been? That would’ve been bad, very bad…